This article is part of a series. Solution is #5 of 5.

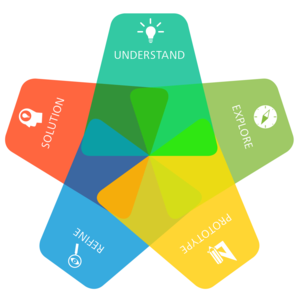

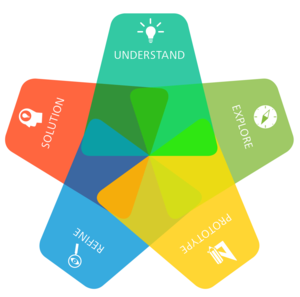

In this series, Michele Ronsen of Ronsen Consulting explores Design Thinking through blogs and activities. Before reading the article below, check out the first four blogs in the series, which cover the Understand, Explore, Prototype, and Refine phases of Design Thinking.

Welcome to the fifth and final blog article about Autodesk’s five-step Design Thinking Process: Solution. This is where you present your final work. Doing this well is just as valuable as producing outstanding work, if not even more so. It’s paramount that you do not underestimate the importance of this final deliverable. In fact, work that’s presented thoroughly and expertly will often outshine work that isn’t as well done. Why? Several reasons:

A successful presentation will bring people together and encourage rich dialog and deep connection.

Shared experience is greater than any individual experience and possesses the power to align disparate views and gives the opportunity to progress those views with a unified vision.

Presenting your recommendation is sometimes your last opportunity to influence your audience’s beliefs and behaviors.

While these are benefits for both you and the audience you’re presenting to, keep in mind that building your final presentation is also a chance for you to step back, review your own process; identify, document and demonstrate how you arrived at your recommendation. These are critical steps to building out the project for inclusion in your portfolio; this work also can live on ad infinitum as a case study for your own design thinking process.

We’re going to apply the Solution phase to an actual project. The assignments that correspond to this blog article are tied to the Disaster Relief project. In this challenge, you will design a disaster relief shelter that's strong enough to withstand the elements—and gives real-world comfort to people in a time of crisis—using Revit, a building design software specifically built for Building Information Modeling (BIM), including features for architectural design, MEP and structural engineering, and construction.

As with the first four steps in this series—Understand, Explore, Prototype, Refine—in this phase, we have three levels of assignments to complement this challenge. Beginners will build an easy to assemble disaster shelter. Inter- mediates will create a transitional family shelter from local materials. Advanced practitioners will design a durable family shelter to withstand natural disasters.

Let’s revisit the first four steps of Autodesk’s Design Thinking Process and apply them to building and delivering a great presentation simultaneously. With this project, we’ll be looking at designing disaster relief shelters using the full five-step process. What you’ll see in this final step, is that the Solution and its presentation circle back and leverage the first four steps again. Let’s dig a little more into that.

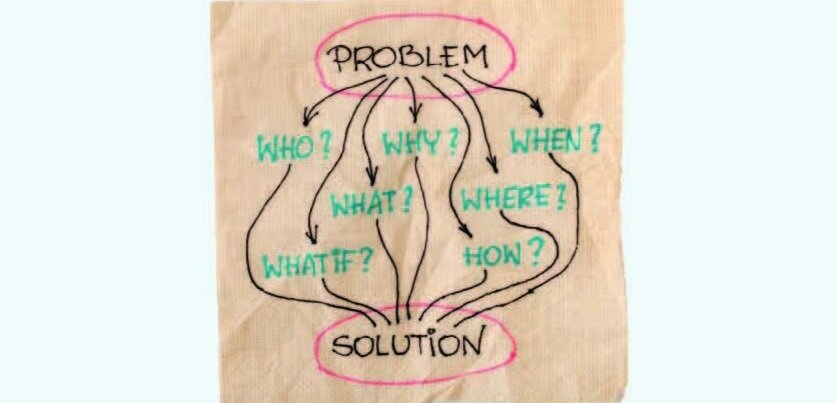

Understand

We know Understanding is about your audience. Understanding the people you’re presenting to is an essential first step in crafting your final solution. In your presentation, you’ll identify your audience’s wants and needs in order to prepare and frame it properly.

As you know, Understand is the most foundational and important phase of this methodology. Design thinking does not start with a problem or a solution. It is implementing this preliminary step that truly differentiates design thinking from a traditional design approach. Apply it to building your presentation as well. The audience that you’re presenting to may be different than the people you initially interviewed to learn about needs and wants. It may be those people, but it’s most likely leadership and stakeholders, the people who will decide whether or not to implement the solution you’ve designed.

There are both passive and active methods to support Understanding that apply to Solution. You could leverage passive methods by looking at presentations and portfolios from industries, companies and thought leaders you want to work with. Their presentations probably got them an impression that earned them their role. Google their names, look for work posted to their LinkedIn profiles, on personal and corporate websites, blogs, Pinterest, and more. Take note of how these leaders are presenting their work, the formats they use, what you like and don't like about it and what’s similar. Also look for gaps where you can stand out.

You might leverage active methods, asking your audience about their presentation preferences and expectations. Find out about the software and technology available to them, the room you will be presenting in, and their presentation culture and tone. Identify and confirm the goals including which messages and components are most important to cover. Determine if they have a data-driven or a storytelling culture. Find out if they are visual or literal, if your presentation will be in-person or conducted remotely via Skype, GoToMeeting, Slack, or a combination; how much time you have to present, and other pertinent details. Understanding these audience specifics and the nature of the physical, digital, and analog structure will help you define the best strategy for communicating each message, as well as the best channel(s) and disciplines to use.

Explore

Explore your key messages, variations on how to present them, and the formats/channels that will resonate with your audience the most. Generate a wide range of ideas on how you might meet their needs. Consider which approach- es will best communicate your solution and meet the established presentation goals. Make sure to take into account the time you have to prepare for the presentation and be realistic about your bandwidth and skillset.

Some formats to consider may include a slideshow, video, 3D prototype, Pecha Kucha rapid approach, a combination of these, and/or something more unique such as a role-playing experience comparing before and after scenarios. Generate a range of messaging, design and format ideas.

Weigh the complexity of your desired approach against the time you think you will need to develop the presentation and the supporting components. Then triple the hours you think it will require. Before you make a final decision, ask yourself if you honestly have the time and skills to not only pull it off but to blow it out of the water! Be extremely honest with yourself before you embark on your chosen direction.

Prototype

Prototype your presentation. This is about turning your presentation ideas into form in order to validate the approach. It’s about gathering your thoughts, key messages and other materials into a usable state in the format(s) you’ve chosen to pursue. It includes practicing your presentation, within the timeframe allotted, using the aids you’ve created, and soliciting feedback from others on the individual components and collective presentation experience. The desired result is to provide you a sense of the whole presentation in order to gather constructive and timely feedback to improve it well before the deadline. Practice is an absolute. Plan to rehearse your presentation several times before performing it for others to comment. Make sure you save each version of your work in multiple formats just in case!

Here are some sample questions to consider as you build your interview protocol:

Front-loading

What do you think the goals of this presentation are?

Do you think this format/channel is the most appropriate for the audience?

Evaluating

Are all of the graphics related to the topic? Are they all needed?

Which graphics make it easier to understand the presentation and support my conclusions Which don't?

What are the three weakest aspects of the presentation?

What are the three strongest aspects of the presentation?

How sequential and logical was the presentation?

What could make this a higher quality presentation?

Does the presentation utilize available technology effectively?

Did I speak too quickly or softly?

Reflection

How engaged did you feel in the presentation?

How effectively does the presentation convey the meaning and purpose?

What is the most important component for me to address in order to improve the presentation?

Do you think this format/channel is the most appropriate for the audience?

How effective was the presentation?

Make sure to record your interviews. When you are soliciting feedback take note of all of the questions people ask as well. Anticipate your audience asking you these questions during your presentation so you can prepare answers to them before delivering your final.

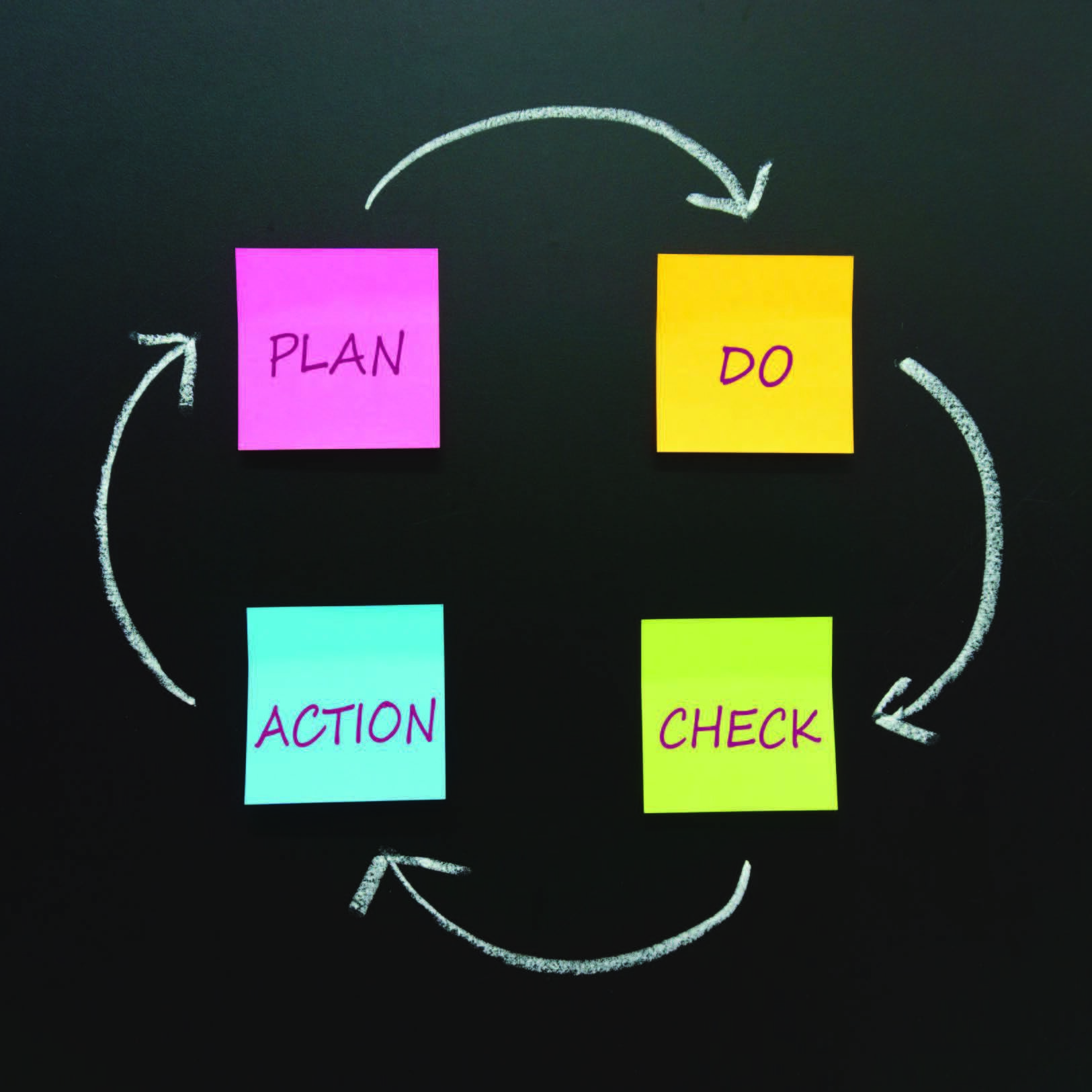

Refine

Refine your presentation approach, key messages, format and any other artifacts to ensure they are meeting the presentation’s goals. Make sure you have previous versions backed up in multiple formats… just in case! Take a fresh look at your highest fidelity presentation and artifacts, review them, and note the following:

How well the criteria is met

If the timeframe allotted matches the time needed

How much time is left before delivery for additional refinement

Remember, the goals may have morphed through the process, or it’s possible that you may have departed from the destination accidentally, or you might be running out of time. It happens to the best of us! Be brutally honest with yourself and your abilities too. Did you learn that you are not comfortable speaking in front of a large audience?

Consider recording your presentation’s audio ahead of time. Did you learn that a 3D prototype resonated more than the static detailed rendering? Contemplate diverting more effort into that than another aspect. Refine your approach accordingly and continue to rehearse.

Solution

Solution is the final and last phase in the process. By this point, you’ve practiced each of the previous steps, invested lots of time in your design challenge, understand the importance of presenting your work well and engaging with your audience, and rehearsed and revised your presentation several times. You’ve also applied Design Thinking to multiple disciplines and seen how the approach can be applied to a variety of challenges and situations.

Here we are at Solution. This is your final opportunity to shine, show your wares and influence your audience. This is where the rubber hits the road! Go get ‘em! Don't forget to:

Gather all of your final materials the night before (digital and analog)

Save and bring them with you in multiple formats (just in case!)

Review and iron out any last minute logistics (transportation, technology, etc.)

Dress for success

Get a good night’s sleep

The day of the final presentation, plan to arrive at least half an hour before your meeting time. During your presentation smile, speak clearly, make frequent eye contact and do not read from your slides or notes. Try to connect with your audience, explain how you’ve solved the challenge succinctly, ask for feedback, and thank them for attending.

After the presentation, write down what worked well, what didn’t, and what you would change if you have another opportunity to present the same work. Then make a separate note about how to best incorporate this work into your portfolio while it’s fresh in your mind. Last but not least, share your work on Autodesk Design Academy here.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this entire blog series and all of the related assignments on Autodesk’s Design Thinking Process. I commend you for taking the initiative to learn the new skills required to excel as a designer today.

In true Design Thinking spirit, we welcome your thoughts on how we can improve this series, what we can add to it or clarify, and how we can make it more meaningful to educators and students like yourself. Please share your feedback by emailing designacademy@autodesk.com.

Test your complete set of Design Thinking skills with this activity.